BANJUL (GAMNA) 18/02/24 - A veteran politician and former minister during the PPP regime, Alhaji Kalilu Fodayba Singhateh, was a member of The Gambian delegation that attended the Marlborough House talks in London in 1962 to negotiate The Gambia’s independence.

Speaking in an exclusive interview, Alhaji Kalilu spoke of the challenges they encountered. In fact, he reported that during the talks, the delegation was divided, as some delegates were opposed to the idea of Gambia’s independence.

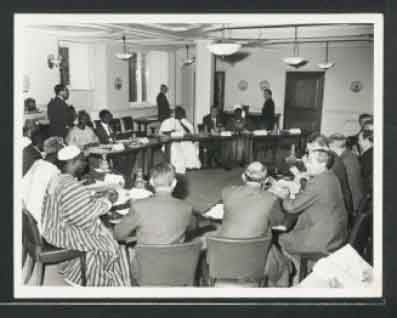

The delegation included members of the governing party, opposition leaders, members of civil society, workers’ representatives, and the Commonwealth Secretary General.

He revealed that Mr. Pierre Sarr Njie was by then the Chief Minister, and other delegates included E D Njie, I A S Burang-John, Kebba Wally Foon, Momodou Cadi Cham, Reverend John Colley Faye, Ibrahima Muhamadou Garba-Jahumpa, Mrs. Racheal Palmer, Momodou Ebrima Jallow, Sheriff Saikouba Sisay, Sheriff Mustapha Dibba, Famara Wassa Touray, Amang Kanyi, and Sir Dawda Kairaba Jawara. The delegation was led by the Governor General, Sir John Paul.

Alhaji Kalilu Singhateh expressed their determination in the London negotiations to deliver independence to the Gambians and that there was no other option for them.

He said, ‘‘Sir Dawda produced a blueprint for independence that guided us, and we also had the support of Governor General Sir John Paul, who was very understanding.’’

Alhaji Kalilu stated that the instrument of independence was later handed to Prime Minister Sir Dawda Kairaba Jawara on February 18, 1965, at McCarthy Square, where the Union Jack was lowered and the Gambian flag hoisted.

Teething Post-Independence Challenges

The senior statesman and diplomat pointed out that the initial challenge after gaining independence was limited resources and capacity; there were not enough educated Gambians to take up positions, so they had to continue working with British officials until they had competent people to take over.

Education

Commenting on the education system, Alhaji Kalilu said that during their school days, parents were very reluctant to send their children to school because of the fear that their children might be westernised to the extent that they would disregard religion, tradition, and other cultural values.

He stated, ‘‘Our parents felt that western education was not suitable for the upbringing of children. However, the colonialists at that time felt western education would be useful for the development of the country, so they convinced the chiefs to send their children to school. This led to the establishment of Armitage High School in Jangjangbureh (then Georgetown) in the then Macarthy Island Division, now Central River Region’’.

‘‘Armitage High School,’’ he continued, ‘‘was later transformed and made accessible to all, and students from the provinces were sponsored by their respective area councils’’.

He added that in those days, all the primary schools in the provinces were built in the home villages of the chiefs so that they, the chiefs, led the way by enrolling their children, and the rest of the community followed.

Mr. Singhateh pointed out that although his father was not a chief, he was a close associate of Chief Janko Kinteh of Kinteh Kunda. He noted that he happened to be one of the few lucky Gambians to acquire western education during the colonial era.

‘‘The Kinteh Kunda School was built in 1932, but the intake was very low because people’s attitudes towards western education were hostile. The school had to be closed, although it was later reopened after the Second World War in 1945,’’ he further narrated, adding that he was among the first intakes. He said over the years, people became less hostile to western education, and later, the enrollment rate increased to about 40 students.

He recalled that at the time, there were about 35 primary schools—the same number of districts in the country.

‘‘We also had mission schools at Kristi Kunda, Bwiam, and Bathurst, among others,’’ he added.

On how people perceived the idea of sending girls to school, Alhaji Kalilu said that in those days, girls were meant for domestic work and marriage. He observed that, due to their lack of western education, Gambian women’s participation in politics was limited.

Further commenting on schools, Alhaji Kalilu said that during their school days, the school was also regarded as a training and reforming institution for stubborn students. He made the example of Seyfo Alhaji Abou Khan of Kuntair in the Jokadu district, who was given the responsibility of reforming stubborn juveniles instead of sending them to jail.

When asked about the relationship between teachers, parents, and students, Alhaji Kalilu said that although there were very few schools, the relationship between teachers, parents, and students was excellent.

‘‘Parents saw schools as training centres to enforce discipline and inculcate knowledge. They cooperated with teachers and never interfered in the disciplinary process—in fact, parents would further punish their children when teachers reported their bad behavior. Eventually, students were afraid of their parents but also had high respect for their teachers. It was a very cordial relationship, which worked well,’’ he emphasised.

He observed that the education system during their school days was different from the current school system.

‘‘Students in those days had to go through sub-standards 1, 2, and 3 before going to standard 1. You have to pass all subjects to get to the next standard, because failing even a single subject would disqualify a student. Spellings, numbers, letters, singing, and physical training were all subjects, and one had to pass them all to be promoted to the next standard. Even students who stopped at standard 3 or 4 were employable, and those who reached standard 7 were very advanced and could be employed to top positions,’’ he explained.

Political engagements

When asked what motivated him to go into politics, he said people had been involved in political activities in the country from 1924 up to the 1950s, although it was limited to Banjul (then Bathurst) and the Kombo Saint Mary Island.

During the time of Universal Adult Suffrage in 1960, the political arena was widened, and that was how he got into politics.

‘‘Before, the active politicians were Edward Francis Small, Ousman Jeng, John Colley Faye, St. Clair Joof, Ibrahima Mohumadou Garba-Jahumpa, Hendry Madi, and Oldfield, among others. The Protectorate People’s Party was formed in 1959, but there were only eight constituencies before 1962. However, Jawara and the PPP cried foul after the 1960 elections and wrote a petition. Another election was held in 1962, and this time, the seats increased from 8 to 13. The PPP contested and won all seats, and Sir Dawada Jawara became Premier,’’ he stated.

Women’s participation

Mr. Singhateh revealed that the first female candidate to contest elections in The Gambia was Lady Augusta Jawara, the ex-wife of Sir Dawda Jawara. She was nominated by the PPP to contest the Jollof and Portuguese Town constituencies but lost to the candidate of the United Party (UP), Mr. Kebba Waly Foon. At that time, no other party had female candidates—the PPP was the first political party to nominate a female candidate. “We respected women’s position in the party and realised that they deserved more than clapping and dancing.”.

While the first female minister was Mrs. Louise Njie, the first elected female candidate was Mrs. Nyimasata Sanneh Bojang, who also contested on a PPP ticket and served in a ministerial position.

However, he asserted that “the best gift The Gambia had from the colonial government was a competent civil service, although there was no money. Even university graduates employed as civil servants were made to go through the ranks. That way, they gained experience, commitment, and loyalty’’.